Flaring from Oil & Gas Production

Flaring from Oil & Gas Production

Per the World

Bank, the world currently flares roughly 3.25 tcf of natural gas per year. Some of these flares are visible from

satellite pictures, as shown in Figure 1.

The World Bank has solicited support to end this flaring

by 2030, and a number of countries and companies have signed on to the

initiative. Progress has been made (see Figure 2),

however, there is still much work to be done.

Figure 2 - Long-term gas flaring trend (World Bank)

This goal will require multiple solutions to eliminate

routine gas flaring and unless these are commercially viable solutions, it is

difficult to imagine that this initiative will succeed. Three challenging examples are described

below.

Shale Oil Wells

Shale oil wells, seen in Figure 3

& Figure 4,

typically:

·

have a very short life (18 months to three

years)

·

low production rate per well (<1500 barrels

per day)

·

are spaced a few miles apart

·

are located in remote areas, and

their associated

gas rates (< 1 mmscfd) are generally so low that conventional solutions for

recovery are uneconomical .

Figure 3 - Sample Shale Oil Field

It is for this reason that the Texas

legislature, for example, exempts collection of or even flaring of gas

where the flare rate is less 50,000 scfd from an individual well.

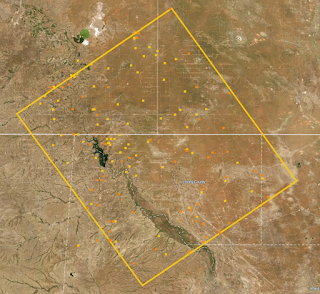

Figure 4 – Fall 2021 Methane Emission in Western

Permian Basin

Stranded Gas

Further, trillions of cubic feet of Natural Gas are

stranded in remote harsh environments world-wide where conventional solutions

for recovery are currently not viable.

The Oil & Gas industry has made great strides in

eliminating routine flaring from large facilities by either collecting the gas

from multiple fields and liquifying it into liquified natural gas (“LNG”) or

re-injecting back into the reservoir.

But there are a number of challenges that have to be

over-come.

·

In certain parts of the world, where there is considerable

civil unrest, the pipe-line networks are routinely destroyed and the LNG plants

become inoperable.

·

In other parts, the on-shore gas plant, not

operated by the Oil company, may fail due to any number of reasons and be

incapable of receiving the gas.

·

For certain formations, it is not possible to

re-inject or continue to re-inject the gas.

·

Gas re-injection can require extremely

high-pressure compressors requiring significant power and space which the

existing facilities may not be able to accommodate.

Figure 5 - OSO complex operated by ExxonMobil in Nigeria (Business Wire)

In the example shown in Figure 5,

the Oil company had to build additional bridge-connected platforms to collect

portions (LPG) of the flared gas at significant cost. Even then, the gas had to be sent to

shore. While this is practical for

certain fields such as Oso, which is located near the Bonny Island LNG plant,

it is not viable for all. Thus, often in

modern field developments, the gas is re-injected at negative NPV for the

overall development from:

·

Capital and operating cost for the gas

compression, associated processing (gas dehydration), power, utilities and

chemicals

·

Capital cost for drilling the injection well(s)

·

Capital cost for the subsea, risers, umbilicals,

and flowlines

As well as lost potential revenue from the injected

gas.

Eventually (typically 7 years), the injected gas

breaks through the formation and the produced Oil to Gas ration is further

reduced (in favor of the gas) making the project less and less commercially

attractive.

Thus, at some point in the future, there will be a

great number of fields currently in use, where the re-injected gas will become

stranded.